Saturday, January 31, 2015

Saudi Kremlinology: what does King Salman's reshuffle mean for the future?

One week into his reign, Saudi Arabia’s new king announced a major government shakeup, catching insiders by surprise and consolidating his hold on the throne

The Guardian

One week into his reign, Saudi Arabia’s new king has reshuffled senior government officials, catching insiders by surprise and starting a “Kremlinology”-style dissection of what the new names mean for policy and direction.

With a series of royal decrees issued late on Thursday, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud has consolidated his hold on the throne with a number of senior appointments that could take the country in a new direction.

Among the most significant of the 30 new names is Adel al-Teraifi, who has been named information minister after being plucked from the secular Dubai-based TV channel, al-Arabiya. Teraifi has a Phd from the London School of Economics and an outlook that is at odds with the clerical establishment, which is prominent in Saudi affairs.

An adviser to the royal court suggested that the appointment of Teraifi was a nod to a need for the kingdom to be more responsive to criticism and inclusive of demands from a younger generation ever more accustomed to fast-paced news and information.

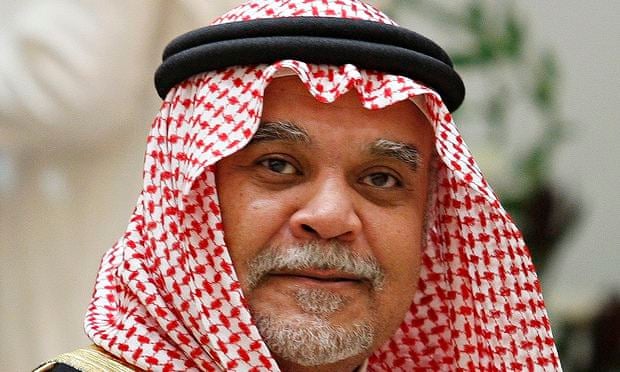

Key security officials have also been changed. Removed from any role is the once powerful Prince Bandar bin Sultan, a former intelligence chief and ambassador to the US, who was long hailed for his links to Washington, but had fallen from grace in the past year over the perceived failure of his Syria policy.

New committees have been set up to oversee security and political affairs. King Salman also fired two sons of the late monarch, King Abullah: Prince Mishaal, who acted as governor of Mecca, and Prince Turki, who ran Riyadh province.

To the relief of markets around the world, the kingdom’s oil and foreign ministers remain unchanged. The decision to keep the ministers in place is being widely interpreted as a sign that the new king has given both ministries a “business as usual” mandate.

King Salman earlier in the week suggested there would be no major change to Saudi Arabia’s direction. However, with an estimated 60% of Saudi citizens under the age of 21, he is known to fear the demands of a new generation. Equally troubling for the 79-year-old monarch is growing regional turmoil, in particular the increasing presence of the Islamic State (Isis) terror group, which partly draws its legitimacy from a hardline reading of Islam espoused by some Saudi clerics.

Since its inception as a nation state, the House of Saud has had an accommodation with the clerical establishment, which allows it to run the affairs of state in return for clerics defining the national character.

Throughout the 83-year history of the modern state, rulers have been resistant to western demands for reform and Salman has vowed no major change in approach. “We will continue adhering to the correct policies that Saudi has followed since its establishment,” he said in a nod to the clerical leaders.

However, Salman has also said that his late half-brother’s cautious reforms – seen as painstaking and begrudging by critics – were necessary and should continue. Dissent remains severely limited throughout the kingdom, as do women’s rights and freedom of expression. Human rights officials say the appointment as deputy crown prince of Mohammed bin Nayef – who drove many of the hardline stances – showed that real reform was not on the new agenda.

As evidence of that, Amnesty International pointed to mooted pardons announced by King Salman for “public rights” convictions, which would be determined by the interior minister.

“This is akin to the fox guarding the henhouse,” said Philip Luther, Amnesty’sMiddle East and North Africa programme director. “Since the ministry of interior has been the main authority implicated in silencing activists and imprisoning them in the first place.”

The slaying of the Saudi spider

David Hearst

Blowing away the cobwebs also means dealing with the spider. Prince Bandar bin Sultan has been stripped of his last remaining role as head of the National Security Council. This, one senses, really is the end of the line for Bandar, and the region will be all the more stable for it.

Abdullah's two sons, Prince Mishaal bin Abdullah, who is the governor of Mecca, and Prince Turki, who governed the capital Riyadh, have been dismissed. Abdullah's only son left in power is Prince Muteb, who stays as head of the National Guard. There is no love lost in this family.

A conservative cleric, Saad al-Shethri, who backed gender segregation in higher education, has become Salman's personal adviser. But a balance has been struck with the addition of the new information minister, Adel al-Toraifi, a young liberal who is a former head of Al Arabiya news channel.

The two men to emerge with the power to run the country are Mohammed bin Nayef, the deputy crown prince, and Salman's son Mohammed, who now has three roles: defense minister, general secretary to the royal court, and president of the newly formed Council of Economic and Development Affairs. Another Salman son, Abdulaziz, is deputy petroleum minister. The second generation has now been firmly secured by the Sudairi clan.

Salman started his reign by buying the love of his people, the same thing the late King Abdullah tried to do during the first months of the Arab Spring. All state employees will receive two months of bonus salary, and all retired state employees will receive two months of bonus pension. Students who receive state grants and those on social security will get two months of extra funds as well. The bill comes to a mere $30 billion.

"Dear people: You deserve more and whatever I do I would not be able to give you what you deserve," the newly inaugurated monarch said on Twitter, just a few weeks after Riyadh signaled it would have to cut back on public spending because of the oil-price crash. Salman was retweeted 250,000 times.

King Salman has had rave reviews. All manner of former opponent of King Abdullah are now singing Salman's praises. Informed Saudi observers note that King Abdullah became dogmatic in his last years. Salman, for them, marks a return to the moderation of King Fahd.

The new king stressed continuity, but his first seven days in power have been anything but. And the gear change will be noted first abroad. In a world in which personal relations play out in politics, it is important to remember who Salman's and Bin Nayef's friends are.

King Salman has remained close to Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad, the emir of Qatar, so the threat that Saudi Arabia made last year to lay siege to its tiny neighbor or have it expelled from the Gulf Cooperative Council now looks like a bad memory. Similarly, bin Nayef is close to senior Turkish officials, Saudi sources tell me.

The rift between Turkey and Saudi Arabia after the Arab revolutions of 2011 will have pained him, not just because the two regional powers need each other to contain Iran's expanded influence in Iraq, Yemen, Lebanon and Syria but personally. It is likely that he will repair that rift.

It is also payback time for bin Nayef's personal enemies. The interior minister has still not forgotten that two-hour conversation that the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Zayed, had with Richard Hass 12 years ago, which we know about courtesy of WikiLeaks. Speaking about bin Nayef's father, who was the Saudi interior minister at the time, the Emirati prince observed that Darwin's theory that man was descended from the apes was correct.

Bin Nayef, the son, has more recent scores to settle with Abu Dhabi's ruler. Erem News, which, like every Emirati news outlet, is controlled by the royal court, questioned bin Nayef's appointment as deputy crown prince. Saying that Salman failed to consult the Allegiance Council, the UAE mouthpiece noted, "The mechanism of choosing Mohammad Bin Nayef from among several prominent grandsons has attracted the attention of observers."

This was not a casual post. An Egyptian TV anchor, Yousef Al-Hosseini, tried the same thing on as soon as Abdullah's latest illness became known. According to Arab Secrets, this was part of a campaign masterminded by the ousted Khaled al-Tuwaijri, Abdullah's confidant, to keep Prince Meteb lined up for the role of deputy crown prince. The website named the route through which the anchor's script was dictated, from the Saudi royal court through to Sisi's office manager, Abbas Kamil, the man who has been secretly recorded asking for the satirist Bassim Yousef to be taken off the air.

Tuwaijri, Bandar and bin Zayed ran out of time. The king died before a serious challenge to Salman could be mounted. And now two of them, at least, are yesterday's men. We will watch with interest what happens to the third. This food chain of intrigue from Riyadh to Cairo is likely to be broken.

The changes taking place in the Saudi royal palace are already having their effect. Bin Zayed stayed away from Abdullah's funeral, as did the Egyptian president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. And just at the time when Sisi needs a fresh injection of Saudi cash, Egypt is more unstable than ever, with full-scale military operations in the Sinai and mass protests around the country that never seem to die down. The Egyptian Pound is at an all-time low. The options for Sisi appear to be narrowing.

This is not a good time for the Egyptian army to lose its chief bankroller in Riyadh, but this now is a real possibility. Even if bin Nayef decides to keep the funds going - and there was always a difference between funds promised and hard cash received - it may now come with strings attached.

The policy of declaring the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization may also be about to change. Salman himself received Sheikh Rached Ghannouchi, the leader of Ennadha, in his condolences for the late king. This is the most senior Islamist to be welcomed in Saudi Arabia. The removal of Suleiman Ab Al-Khail as the minister of endowments and Islamic affairs, who was an arch opponent of the Brotherhood, is another sign that the policy might be about to change.

Even if it doesn't, the outcome of the earthquake this week in Saudi Arabia will be received with quiet satisfaction by senior foreign office officials who bridled at David Cameron's launching of an inquiry into the Brotherhood in Britain, which was done under Saudi and Emirati pressure.

Up until Salman took over, the inquiry headed by Sir John Jenkins has proved to be a political embarrassment. It has been unpublishable because it came to the "wrong" conclusion, clearing the Brotherhood of any involvement in terrorism in Egypt. Now the new masters of Riyadh might even welcome such a conclusion.

This article was first published by the Huffington Post

CIA and Mossad killed senior Hezbollah figure in car bombing

AN IMPORTANT STORY

The Washington Post

Link

A Lebanese Hezbollah supporter holds a poster of Imad Mughniyah during a rally in the southern suburb of Beirut on Feb. 16, 2009, to commemorate the first anniversary of the slain Hezbollah commander’s death. (Hussein Malla/Associated Press)

Rescuers survey the damage sustained by the U.S. Marine barracks a day after a suicide truck bomb exploded at the site near the Beirut airport in October 1983. (Zouki/AP)

The Washington Post

Link

On Feb. 12, 2008, Imad Mughniyah, Hezbollah’s international operations chief, walked on a quiet nighttime street in Damascus after dinner at a nearby restaurant. Not far away, a team of CIA spotters in the Syrian capital was tracking his movements.

As Mughniyah approached a parked SUV, a bomb planted in a spare tire on the back of the vehicle exploded, sending a burst of shrapnel across a tight radius. He was killed instantly.

The device was triggered remotely from Tel Aviv by agents with Mossad, the Israeli foreign intelligence service, who were in communication with the operatives on the ground in Damascus. “The way it was set up, the U.S. could object and call it off, but it could not execute,” said a former U.S. intelligence official.

A Lebanese Hezbollah supporter holds a poster of Imad Mughniyah during a rally in the southern suburb of Beirut on Feb. 16, 2009, to commemorate the first anniversary of the slain Hezbollah commander’s death. (Hussein Malla/Associated Press)

The United States helped build the bomb, the former official said, and tested it repeatedly at a CIA facility in North Carolina to ensure the potential blast area was contained and would not result in collateral damage.

“We probably blew up 25 bombs to make sure we got it right,” the former official said.

The extraordinarily close cooperation between the U.S. and Israeli intelligence services suggested the importance of the target — a man who over the years had been implicated in some of Hezbollah’s most spectacular terrorist attacks, including those against the U.S. Embassy in Beirut and the Israeli Embassy in Argentina.

The United States has never acknowledged participation in the killing of Mughniyah, which Hezbollah blamed on Israel. Until now, there has been little detail about the joint operation by the CIA and Mossad to kill him, how the car bombing was planned or the exact U.S. role. With the exception of the 2011 killing of Osama bin Laden, the mission marked one of the most high-risk covert actions by the United States in recent years.

U.S. involvement in the killing, which was confirmed by five former U.S. intelligence officials, also pushed American legal boundaries.

Mughniyah was targeted in a country where the United States was not at war. Moreover, he was killed in a car bombing, a technique that some legal scholars see as a violation of international laws that proscribe “killing by perfidy” — using treacherous means to kill or wound an enemy.

“It is a killing method used by terrorists and gangsters,” said Mary Ellen O’Connell, a professor of international law at the University of Notre Dame. “It violates one of the oldest battlefield rules.”

Former U.S. officials, all of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the operation, asserted that Mughniyah, although based in Syria, was directly connected to the arming and training of Shiite militias in Iraq that were targeting U.S. forces. There was little debate inside the Bush administration over the use of a car bomb instead of other means.

“Remember, they were carrying out suicide bombings and IED attacks,” said one official, referring to Hezbollah operations in Iraq.

The authority to kill Mughniyah required a presidential finding by President George W. Bush. The attorney general, the director of national intelligence, the national security adviser and the Office of Legal Counsel at the Justice Department all signed off on the operation, one former intelligence official said.

The former official said getting the authority to kill Mughniyah was a “rigorous and tedious” process. “What we had to show was he was a continuing threat to Americans,” the official said, noting that Mughniyah had a long history of targeting Americans dating back to his role in planning the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut.

“The decision was we had to have absolute confirmation that it was self-defense,” the official said.

There has long been suspicion about U.S. involvement in the killing of Mughniyah. In “The Good Spy,” a book about longtime CIA officer Robert Ames, author Kai Bird cites one former intelligence official as saying the operation was “primarily controlled by Langley” and it was “a CIA ‘black-ops’ team that carried out the assassination.”

In a new book, “The Perfect Kill: 21 Laws for Assassins,” former CIA officer Robert B. Baer writes how he had considered assassinating Mughniyah but apparently never got the opportunity. He notes, however, that CIA “censors” — the agency’s Publications Review Board — screened his book and “I’ve unfortunately been unable to write about the true set-piece plot against” Mughniyah.

The CIA declined to comment.

“We have nothing to add at this time,” said Mark Regev, chief spokesman for the prime minister of Israel.

Inside the killing of Imad Mughniyah(2:51)

Seven years after the death of Hezbollah's Imad Mughniyah, The Post's Adam Goldman and the Washington Institute's Matthew Levitt look at the international cooperation that brought down the former military commander. (Davin Coburn, Randolph Smith and Kyle Barss/The Washington Post)

A theory of self-defense

The operation in Damascus highlighted a philosophical evolution within the American intelligence services that followed the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Before then, the U.S. government often took a dim view of Israeli assassination operations, highlighted by the American condemnation of Israel’s botched attempt in 1997 to poison the leader of Hamas, Khaled Meshal, in Amman, Jordan. The episode ended with Mossad agents captured and the Clinton administration forcing Israel to provide the antidote that saved Meshal’s life.

The Mughniyah killing, carried out more than a decade later, suggested such American hesitation had faded as the CIA stretched its lethal reach well beyond defined war zones and the ungoverned spaces of Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia, where the agency or the military have deployed drones against al-Qaeda and its allies.

A former U.S. official said the Bush administration relied on a theory of national self-defense to kill Mughniyah, claiming he was a lawful target because he was actively plotting against the United States or its forces in Iraq, making him a continued and imminent threat who could not be captured. Such a legal rationale would have allowed the CIA to avoid violating the 1981 blanket ban on assassinations in Executive Order 12333. The order does not define assassination.

In sanctioning a 2011 operation to kill Anwar al-Awlaki, a U.S. citizen andan influential propaganda leader for al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Yemen, the Justice Department made a similar argument. Noting that al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula had targeted U.S. commercial aircraft and asserting that Awlaki had an operational role in the group, government lawyers said he was a continued and imminent threat and could not feasibly be captured.

“It’s fairly clear that the government has at least some authority to use lethal force in self-defense even outside the context of ongoing armed conflict,” said Stephen I. Vladeck, a professor of law at American University’s Washington College of Law. “The million-dollar question is whether the facts actually support a determination that such force was necessary and appropriate in each case.”

The CIA and Mossad worked together to monitor Mughniyah in Damascus for months prior to the killing and to determine where the bomb should be planted, according to the former officials.

In the leadup to the operation, U.S. intelligence officials had assured lawmakers in a classified briefing that there would be no collateral damage, former officials said.

Implicated in multiple cases

At the time of his death, Mughniyah had been implicated in the killing of hundreds of Americans, stretching back to the embassy bombing in Beirut that killed 63 people, including eight CIA officers. Hezbollah, supported by Iran, was involved in a long-running shadow war with Israel and its principal backer, the United States.

The embassy bombing placed Hezbollah squarely in the sights of the CIA, a focus that, in some respects, foreshadowed the targeting of Mughniyah. In his 1987 book “Veil,” Washington Post journalist Bob Woodward reported that CIA Director William Casey encouraged the Saudis to sponsor an attempt to kill a Hezbollah leader. The 1985 attempt on the life of Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah with a car bomb failed, but killed 80 people, and he fled to Iran. Mughniyah’s brother was among those killed.

Former agency officials said Mughniyah was involved in the 1984 kidnapping and torture of the CIA’s station chief in Lebanon, William F. Buckley. The officials said Mughniyah arranged for videotapes of the brutal interrogation sessions of Buckley to be sent to the agency. Buckley was later killed.

Mughniyah was indicted in U.S. federal court in the 1985 hijacking of TWA Flight 847 shortly after it took off from Athens and the slaying of U.S. Navy diver Robert Stethem, a passenger on the plane. Mughniyah was placed on the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorists list with a $5 million reward offered for information leading to his arrest and conviction.

He was also suspected of involvement by U.S. intelligence and law enforcement officials in the planning of the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia that killed 19 U.S. servicemen.

For the Israelis, among numerous attacks, he was involved in the 1992 suicide bombing of the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires that killed four Israeli civilians and 25 Argentinians, and the 1994 attack on a Jewish community center in the city that killed 85 people.

“Mughniyah and his group were responsible for the deaths of many Americans,” said James Bernazzani, who was chief of the FBI’s Hezbollah unit in the late 1990s and later the deputy director for law enforcement at the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center.

The Bush administration regarded Hezbollah — Mughniyah, in particular — as a threat to the United States. In 2008, several months after he was killed, Michael Chertoff, then secretary of homeland security, said Hezbollah was a threat to national security. “To be honest, they make al-Qaeda look like a minor league team,” he said.

Beginning in 2003, Hezbollah, with the assistance of Iran, began to train and arm Shiite militant groups in Iraq, which later began attacking coalition forces, according to Matthew Levitt, who recently wrote a book about Hezbollah and is director of the Washington Institute’s Stein Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence.

The Hezbollah-trained militias proved to be a deadly enemy, wounding or killing hundreds of American troops. As the situation in Iraq deteriorated and coalition casualties spiked in 2006, the United States decided it had to stanch the losses.

The Bush administration issued orders to kill or capture Iranian operatives targeting American troops and attempting to destabilize Iraq. It also approved a list of operations directed at Hezbollah, officials said. The mandate applied directly to the group’s notorious international operations chief.

“There was an open license to find, fix and finish Mughniyah and anybody affiliated with him,” said a former U.S. official who served in Baghdad.

In January 2007, Bush, in an address to the nation, singled out Iran and Syria, two countries with the closest ties to Hezbollah.

“These two regimes are allowing terrorists and insurgents to use their territory to move in and out of Iraq,” Bush said. “Iran is providing material support for attacks on American troops. We will disrupt the attacks on our forces. We will interrupt the flow of support from Iran and Syria. And we will seek out and destroy the networks providing advanced weaponry and training to our enemies in Iraq.”

Shortly after Bush’s speech, Hezbollah’s involvement in Iraq became clearer. On Jan. 20, 2007, five American soldiers were killed in Karbala. That March, Ali Mussa Daqduq, a senior Hezbollah operative with ties to Mughniyah, was captured by the British along with two others and turned over to U.S. forces.

While in U.S. custody, Daqduq confessed to playing a key role in the killing of the soldiers and provided the United States with a deeper understanding of Hezbollah’s networks, said Peter Mansoor, a retired Army colonel who served as executive officer to Gen. David H. Petraeus, the top American commander in Iraq.

“In interrogations with these folks, we finally discovered the full nature of Iranian and Hezbollah involvement in Iraq,” Mansoor said, noting that by then Iran had “outsourced the advisory effort to Hezbollah.” Mansoor said he had no knowledge of the operation that killed Mughniyah.

U.S. officials said Mughniyah played a pivotal role in linking Hezbollah to the Shiite militias that were working with Iran. It remains unclear if he ever entered Iraq. One former U.S. senior military official said there was information he traveled to Basra in southern Iraq in 2006, but it was not confirmed.

Ryan C. Crocker, the U.S. ambassador in Iraq when Mughniyah was killed, said: “All I can say is that as long as he drew breath, he was a threat, whether in Lebanon, Iraq or anywhere else. He was a very intelligent, dedicated, effective operator on the black side.”

Crocker said that he didn’t know anything about the operation to kill the Hezbollah operative and had doubts about Mughniyah traveling to Iraq. That said, he added: “When I heard about it, I was one damn happy man.”

Rescuers survey the damage sustained by the U.S. Marine barracks a day after a suicide truck bomb exploded at the site near the Beirut airport in October 1983. (Zouki/AP)

Terrorism discussion widens

U.S. officials had explored ways to capture or kill Mughniyah for years. Those scenarios gained new urgency in the years after the Sept. 11 attacks when the Bush administration turned to the CIA and the U.S. military’s elite Joint Special Operations Command for stepped-up plans to stop major terrorist operatives — including those without ties to al-Qaeda or the 9/11 plot.

A former U.S. official described a secret meeting in Israel in 2002 involving senior JSOC officers and the chief of the Israeli military intelligence service. Amid a broader discussion of counterterrorism issues, the JSOC visitors raised the prospect of killing Mughniyah in such an offhanded fashion that their Israeli hosts were stunned.

“When we said we would be willing to explore opportunities to target him, they practically fell out of their chairs,” the former U.S. official said. The former official said that JSOC had not developed any specific plan but was exploring scenarios against potential terrorism targets and wanted to gauge Israel’s willingness to serve as an evacuation point for U.S. commando teams.

The former official said that the JSOC approach envisioned a commando-style raid with U.S. Special Operations teams directly involved, not the sort of cloak-and-dagger operation that occurred years later.

“It never went anywhere,” said the former official, who was unaware of the CIA-Israeli operation to kill Mughniyah.

Still, the 2002 encounter suggests that Mughniyah continued to be a focus for U.S. counterterrorism officials even after their overwhelming attention had shifted to al-Qaeda.

“We never took our eye off Hezbollah, but our plate was full with al-Qaeda,” said Bernazzani, who retired from the FBI in 2008 and said he had no knowledge of the operation to kill Mughniyah.

A window of opportunity

It is not clear when the CIA first realized Mughniyah was living in Damascus, but his whereabouts were known for at least a year before he was killed. One of the former U.S. intelligence officials said that the Israelis were first to approach the CIA about a joint operation to kill him in Damascus.

The agency had a well-established clandestine infrastructure in Damascus that the Israelis could utilize.

Officials said the Israelis wanted to pull the trigger as payback. “It was revenge,” another former official said. The Americans didn’t care as long as Mughniyah was dead, the official said, and there was little fear of blowback because Hezbollah would most probably blame the Israelis.

Amos Yadlin, the former head of Israeli military intelligence until 2010, said Mughniyah was positioned right under the group’s leader Hassan Nasrallah.

“He was the commander and chief of all military and terror operations,” Yadlin said, who declined to discuss Mughniyah’s demise. “He was the agent of the Iranians.”

The operation to target Mughniyah came at a time when the CIA and Mossad were working closely to thwart the nuclear ambitions of Syria and Iran. The CIA had helped the Mossad verify that the Syrians were building a nuclear reactor, leading to an Israeli airstrike on the facility in 2007. Israel and the United States were actively trying to sabotage the Iranian nuclear program.

Once Mughniyah was located in Damascus, the intelligence agencies began building a “pattern of life” profile, looking at his routine for vulnerabilities.

Mossad officials suggested occasional walks in the evening — when Mughniyah was unescorted — presented an opportunity. CIA officers with extensive undercover experience secured a safe house in a building near his apartment.

Planning for the operation was exhaustive. An Israeli proposal to place a bomb in the saddlebags of a bicycle or motorcycle was rejected because of concerns that the explosive charge might not project outward properly. The bomb had to be repeatedly tested and reconfigured to minimize the blast area. The location where Mughniyah was killed was close to a girls’ school.

One official said the bomb was tested many times at Harvey Point, a facility in North Carolina where the CIA would later construct a replica of Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Officials eventually concluded they had a bomb that could be used with no risk of others being killed or injured.

Mughniyah wasn’t alone in his confidence to operate freely in Damascus. During the operation, the CIA and Mossad had a chance to kill Qassem Soleimani, commander of Iran’s Quds Force, as he and Mughniyah walked together. Soleimani was an archenemy of Israel and had also orchestrated the training of Shiite militias in Iraq.

“At one point, the two men were standing there, same place, same street. All they had to do was push the button,” said one former official.

But the operatives didn’t have the legal authority to kill Soleimani, the officials said. There had been no presidential finding to do so.

When the bomb used to target Mughniyah was detonated, officials estimated the “kill zone” extended approximately 20 feet. The bomb was “very shaped and very charged,” an intelligence official recalled.

There was no collateral damage. “None. Not any,” the official said.

Facial recognition technology, another former official said, was used to confirm Mughniyah’s identity after he walked out of a restaurant in his neighborhood and moments before the bomb was detonated.

After the attack, Hezbollah leader Nasrallah blamed Israel for the killing and swore revenge: “Zionists, if you want an open war, let it be an open war anywhere.”

In fact, the damage to Hezbollah may have been compounded by the fact that the man charged with exacting revenge on Israel was a suspected Israeli asset. He was recently reported to be on trial in a Hezbollah court in Lebanon, but the group’s leader has downplayed the spy’s importance.

In a statement in 2008 after Mughniyah’s death, the office of then Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s office said: “Israel rejects the attempt by terror groups to attribute to it any involvement in this incident. We have nothing further to add.”

State Department spokesman Sean McCormack said at the time: “The world is a better place without this man in it. He was a coldblooded killer, a mass murderer and a terrorist responsible for countless innocent lives lost.”

Inside the intelligence community, a former official recalled, “It wasn’t jubilation.”

“We did what we had to,” the official said, “and let’s move on.”

William Booth in Jerusalem and Greg Miller, Karen DeYoung, Anne Gearan and Julie Tate in Washington contributed to this report.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)